By Kara Cook and Patty Branco for the National Resource Center on Domestic Violence (NRCDV), with contributions from Brittany Eltringham & Casey Keene

The United States is home to 574 Native American tribes. Indigenous folks make up 1.1% of the population in the United States, or 3.7 million people. Despite making up such a small percentage of the U.S. population, the rate of violence for Indigenous people is significantly higher than any other ethnic or racial group. In fact, 4 out of 5 Indigenous women has experienced some form of violence in her lifetime.

When addressing issues impacting Indigenous peoples in the U.S., it is important to keep in mind that we are not talking about a monolith. Indigenous communities in the U.S. encompass many groups including Native Americans, Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians, as well as other Indigenous folks from the territories.

Violence against Native peoples is grossly underreported, leaving public officials, law enforcement, and everyday people like you and I in the dark about this ever-growing epidemic. Gender-based violence (GBV) is a very prevalent issue that Indigenous women face. During the COVID-19 pandemic, these rates only increased. So, what do both GBV and COVID-19 have to do with the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, and Two-Spirit movement?

Gender-based violence and Indigenous women

Indigenous women, in particular, experience violence at the highest rates compared to any other ethnic or racial group. According to the National Institute of Justice, over half (55.5%) of Indigenous women have experienced intimate partner violence in their lifetime. Because of these high rates of violence and high risk of experiencing gender-based violence, Indigenous women are more likely to be abducted or murdered. In addition, Indigenous women are also disproportionately affected by human trafficking.

The National Indigenous Women’s Resource Center, Inc. (NIWRC) is a Native-led national organization dedicated to ending violence against Native women and children. As NIWRC explains, it is important to understand the connection between gender-based violence – including domestic, dating, and sexual violence – and the high incidence of missing and murdered Indigenous women and relatives (MMIWR) in the United States. Gender-based violence, in turn, needs to be understood within a broader context: “This long-standing crisis of MMIWR can be attributed to the historical and intergenerational trauma caused by colonization and its ongoing effects in Indigenous communities stretching back more than 500 years.”

The Indigenous population and COVID-19

In general, Indigenous Peoples experience a more significant burden of noncommunicable and infectious diseases, which is related to social and health inequities caused by invasion and subsequent colonization. Native Americans have experienced substantially greater rates of COVID-19 mortality compared with other racial and ethnic groups. A study by researchers from Princeton University found that Indigenous communities were at higher risk of COVID-19 mortality, brought on by overcrowded spaces on reservations, high rates of poverty, and limited access to high-quality medical care and health insurance. Rates of mortality for Indigenous peoples due to COVID-19 far exceeded those of white, Black, and Latinx individuals. Additionally, Indigenous peoples experience high rates of other diseases including type 2 diabetes, obesity, hypertension, and heart disease, which also increase the risk of contracting COVID-19. Stay-at-home orders in the early months of the pandemic brought on job loss, which exacerbated the financial hardship that Indigenous peoples already face. In this context of increased financial and emotional stress, Indigenous women have reported experiencing higher rates of gender-based violence.

As the above data illustrates, Native communities and other marginalized groups have been disproportionally impacted by COVID-19. In fact, the pandemic magnified existing systemic racial and gender inequities within the U.S. health care system. Health inequities in the United States have deep roots in white supremacy and colonialism. For a greater understanding of how colonization negatively impacts social determinants of health and have brought about disproportionate inequities that detrimentally affect Indigenous Peoples, please see COVID‐19 and Indigenous Peoples: An imperative for action. As advocates against gender-based violence, health equity is our work. For guidance, please see Back to Basics: Partnering with Survivors and Communities to Promote Health Equity at the Intersections of Sexual and Intimate Partner Violence.

So, what is the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, Two-Spirit movement?

The Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, Two Spirit (MMIWG2S) movement was created in response to the significant rates of violence against Native women. As NIWRC reminds us, the crisis of missing and murdered indigenous women and relatives (MMIWR) is not a new problem. What is new, instead, is the recent national recognition of this crisis by the federal government. This political change, in turn, is the result of grassroots organizing efforts by the families, advocates, communities, and Indian Nations of MMIW.

Sadly, the murder rates of Indigenous women are 10 times the national average, with homicide being the third leading cause of death for Native women and girls aged 10-24. Too often, cases of missing and murdered Indigenous women, girls, and two-spirit individuals go unreported or ignored. You may have seen photos of Native women with red hands painted over their mouths. This image has become a symbol of the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, Two-Spirit movement and way to show solidarity to those Indigenous women, girls, and two-spirit individuals who were killed or who are lost and have not been found.

Sadly, the murder rates of Indigenous women are 10 times the national average, with homicide being the third leading cause of death for Native women and girls aged 10-24. Too often, cases of missing and murdered Indigenous women, girls, and two-spirit individuals go unreported or ignored. You may have seen photos of Native women with red hands painted over their mouths. This image has become a symbol of the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, Two-Spirit movement and way to show solidarity to those Indigenous women, girls, and two-spirit individuals who were killed or who are lost and have not been found.

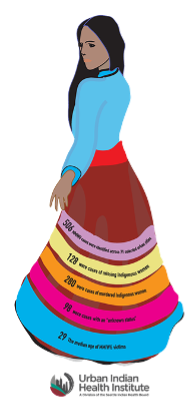

The graphic on the left, created by the Urban Indian Institute, shows statistics found during a study of 71 urban cities and their rates of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls. Researchers put the statistics on a ribbon skirt, which symbolizes the sacredness of the connection between land and Indigenous women. From the top down, the statistics are as follows:

“506 MMIWG cases were identified across 71 selected urban cities;

128 were cases of missing Indigenous women;

280 were cases of murdered Indigenous women;

98 were cases with an ‘unknown status:’ and

29 is the median age of MMIWG victims.”

According to FBI data, in 2023, there were over 5,800 missing American Indian and Alaska Native females reported, with a significant portion being children, and only a fraction of these cases made it into the national database, NamUs, with only 116 cases listed as of May 2024.

The exorbitant rates of missing and murdered Indigenous women are fueled by a thriving human and sex trafficking industry that actively targets these marginalized populations. Many tribal communities reside near borders, which makes them more vulnerable to traffickers because of easy access to seaports, airports, bus and rail terminals, rest stops, truck stops, etc. Additionally, rates of intimate partner violence in the Indigenous community are high, which also serves as a risk factor for the abduction and killing of Indigenous women and girls. Racist myths and stereotypes about Native women (note, for example, how Indigenous women are frequently sexualized in popular media) are intimately connected to the violence inflicted upon them. In the case of MMIW, it leads to prejudicial victim-blaming and widespread indifference toward these victims and their plight.

“When Joyce Echaquan, a 37-year-old Indigenous Canadian woman, began experiencing stomach pains, she checked herself into a hospital in Joliette, Quebec. But she did not get the help she needed. Instead, hospital staff told Echaquan she was stupid, only good for sex, and that she would be better off dead.” – Melissa Godin

The Resilience of Native American People

In the face of violence and oppression, many Indigenous individuals and communities continue to resist, to be resilient, and to thrive. The resilience of Native people draws upon deep connections to culture, spirituality, community, and traditional practices, which act as a protective factor against hardship, particularly in the face of historical trauma and ongoing inequity. Native resilience is often linked to their profound understanding and respect for the natural environment and their strong sense of identity and belonging to the land. Indigenous worldviews, beliefs, values, and practices support individual and community resistance and positive transformation. Re-indigenizing is a pathway to healing and prevention.

“We have much to learn from indigenous populations in the United States, who guard some of our continent’s oldest religions and traditions, are models of human resilience, and share a history of and potential for sustainable action.” – Emma Hubbard

The resilience of her ancestors was not lost on Abigail Echo-Hawk, director of the Urban Indian Health Institute and chief research officer at Seattle Indian Health Board in March 2020 when the federal government answered her call for help. Echo-Hawk and her colleagues sent a request to local and federal partners for masks, testing kits and other resources they needed to protect their community from the spread of COVID-19. Instead, they received a box of body bags intended to bury Indigenous lives lost to the pandemic. She described the delivery as “almost the perfect metaphor for what the federal government has been doing to us for centuries…giving us the things to bury our people in and not giving us the resources so our people can live.” Echo-Hawk turned the body bags (a symbol of death) into a healing ribbon dress filled with symbolisms of hope, strength and resilience, including her own handprints in red ink in solidarity with missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls.

Conclusion

Both COVID-19 and the violence and exploitation endured by Indigenous women must be understood within a context of institutional racism and legacies of colonialism, which has resulted in ongoing racial and gendered violence, government-induced poverty, and health inequity. The elevated COVID-19 death rates documented among Native Americans have served as a glaring illustration of the legacies of historical mistreatment and the continued failure of governments to meet basic needs of these communities. In turn, the crisis of MMIWG2S cannot be decoupled from the historical and present-day contexts of survivors’ lives.

“Understanding the impact of U.S. colonization on Native women is essential to creating the necessary reforms to address the MMIW crisis because current federal law is based upon the laws and policies of earlier eras of U.S. colonization and continue to govern.” – Statement prepared by Jacqueline Agtuca, Elizabeth Carr, Brenda Hill, Paula Julian, and Rose Quilt

As we continue to move through the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, NIWRC has been instrumental in educating advocates about the extent and impact of long COVID (or post-COVID) conditions on Native communities, and how this issue intersects with advocacy and anti-violence work. According to NIWRC, American Indian life expectancy dropped by 6.6 years since 2020, one in 5 people who had covid now have long Covid. With that in mind, we must continue to reflect on the realities of unequal access to protections for groups already suffering, including those who live at the intersections of multiple forms of oppression, and how they are disproportionately impacted by COVID-19.

The National Resource Center on Domestic Violence reminds us that there is “No Survivor Justice Without Racial Justice.” In order to support Native survivors, advocates must understand the historical context of their experiences. There have been many efforts to raise awareness around the tragedy of MMIWG2S. Please read NIWRC’s statement, MMIW: Understanding the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women Crisis Beyond Individual Acts of Violence for a deeper understanding of the issue. Additionally, check out the following tools and resources for more information on how you can support the cause and best address the urgent needs of Native survivors and their communities.

Guides & Toolkits

- When a Loved One Goes Missing: A Quick Reference Guide for Families of Missing Indigenous Women: What to Do in the First 72 Hours by the National Indigenous Women’s Resource Center. This guide gives family and friends of missing Indigenous women information about what they can do when their loved one is missing.

- Missing Indigenous Sisters Tools Initiative (MISTI) by the National Indigenous Women’s Resource Center. This workbook was designed for families to use when a loved one goes missing. In it, there are various worksheets for families to use throughout their search efforts.

- Creating a Human Trafficking Strategic Plan to Protect and Heal Native Children and Youth by the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges offers questions for organizations and individuals to think about in the case of human trafficking in their communities.

- Trafficking in Native Communities by National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges. This guide provides recommendations for communities and the justice system on responding to and preventing human trafficking in Native communities.

Reports & TAQs

- Restoration Magazine Special Edition on MMIW (January 2022). In this Special Edition of Restoration, NIWRC highlights joint efforts to honor MMIW and call for justice for Indigenous women to share examples of organizing actions for National Week of Action and National Day of Awareness for MMIW.

- Colonization, Homelessness, and the Prostitution and Sex Trafficking of Native Women. This paper seeks to illustrate the impact of human trafficking on Native women and girls in our times, with particular attention to the historical context in the United States and the interconnection between trafficking and housing instability.

- How can victim advocates and housing service providers respond to the needs of Native human trafficking survivors? Native women have been on the receiving end of many injustices. These injustices include homelessness and various forms of physical and sexual violence. Native women experience high rates of homelessness. Native women also have the highest rate of domestic violence and rape of any group of women. To support Native survivors, we must understand the historical context of their experiences.

- What are the advocacy needs of American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) Survivors of Gender-Based Violence? The National Resource Center on Domestic Violence (NRCDV), National AI/AN Women’s Resource Center (NIWRC) and the Alaska Native Women’s Resource Center (AKNWRC) convened a workgroup of gender-based violence and housing advocates from Indian country to reflect on the needs of AI/AN survivors. This TAQ outlines some of the needs identified in the workgroup.

Webinars

- Coming Together to Address Human Trafficking in Native Communities: In this webinar, viewers will learn about human trafficking and its effects on the Indigenous population. There are also current resources provided during the webinar.

- Understanding Trafficking to Develop a Local Tribal Response: This webinar gives an overview of how human trafficking shows up in tribal communities. It aims to give viewers different ideas on how to create a response to human trafficking within a tribal community.

- Missing and Murdered Native Women- Public Awareness Efforts: This webinar provides viewers with information around MMIW and how important it is to increase awareness around the issue.

Additional Resources

- Human Trafficking Power and Control Wheel

- National Human Trafficking Hotline

- Special Collection: Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls

- StrongHearts Native Helpline